Kazakhstan’s most revered poet offers the modern world a lesson in wisdom, identity, and balance.

By Jafar G Bua*

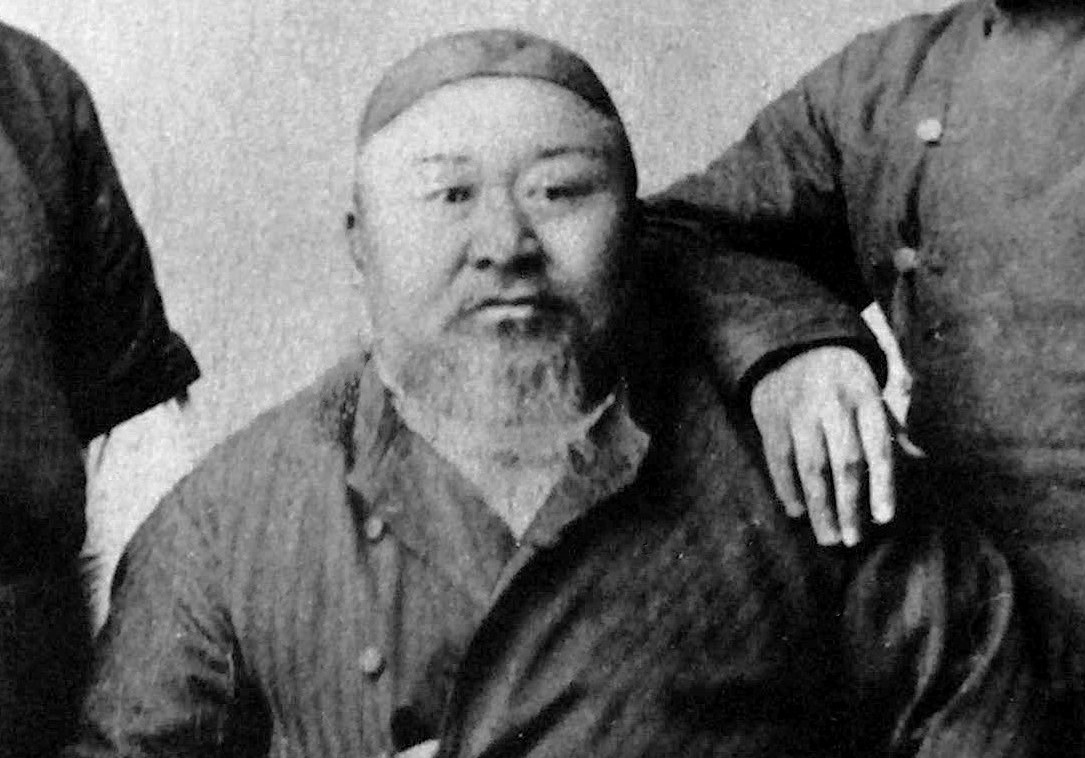

In the open steppes of Kazakhstan, the wind still tells stories. It murmurs across hills where yurts once stood, echoes through ancient trading routes of the Silk Road, and curls around the bronze statues of a quiet man sitting with a book in his lap. His gaze is thoughtful. His name is Abai.

Ask almost any Kazakh — young or old, urban or rural — who shaped their sense of national identity, and the answer is likely to be Abai Qunanbaiuly. He’s not a founding father in the traditional sense. He never led armies or signed treaties. But he shaped something arguably more enduring: the country’s soul.

I first encountered Abai not in a museum or state function, but on a weathered schoolbook in a village outside Shymkent. A boy, no older than ten, was reciting his verses from memory. “A wise man does not raise his voice,” the boy said in Kazakh, looking up with shy pride. “He raises his soul.”

That line has stayed with me.

In a region often misunderstood by the world — reduced to pipelines, steppe stereotypes, or post-Soviet headlines — Abai’s voice offers something both intimate and profound: a portrait of what it means to carry history gently, to honor tradition without becoming imprisoned by it, and to move forward with grace.

Abai was born in 1845 near the Chingiz Mountains, in what is now eastern Kazakhstan. At the time, the region was part of the Russian Empire, and Kazakh nomadic life was under increasing pressure from colonial administration, economic change, and cultural assimilation.

His given name was Ibrahim, but his mother called him “Abai,” meaning “careful” or “thoughtful” — a name that proved prophetic. [1]

Raised in a family of local aristocracy, Abai was expected to become a tribal leader. Instead, he became a thinker. His education straddled both Islamic traditions and Russian Enlightenment thought. He read the Quran, studied Sufism, and later immersed himself in the works of Pushkin, Lermontov, Goethe, and Byron. He translated them into Kazakh not merely as a linguistic exercise, but as a philosophical bridge. [2]

He believed, deeply, that his people could remain Kazakh while also embracing universal knowledge. He didn’t advocate for Westernization. He advocated for awakening.

“Man must think,” he wrote in Kara Sozder (The Book of Words), his collection of 45 essays. “Not follow blindly. He must work, not just wait.” [3]

That sentiment — that dignity comes through self-cultivation — would come to define his legacy.

Published posthumously, Kara Sozder became one of the most influential works in Kazakh literature. In it, Abai offered more than cultural commentary — he offered a national introspection.

He criticized laziness, fatalism, and tribal jealousies. He lamented the erosion of ethics and warned against using religion as superstition rather than spiritual inquiry. But he did so not with disdain, but with an almost fatherly concern.

Abai’s voice was not that of a preacher, but of a guide. He was stern, yes, but also loving — as if every line he wrote was meant to lift a child by the shoulders and say, You are capable of more than you think.

“The words of Abai are not just literary,” says Dr. Gulzhan Kassenova, a historian at Nazarbayev University. “They are ethical, philosophical, even psychological. They’re about how to live with integrity — not only as Kazakhs, but as human beings.” [4]

It’s little wonder that Abai remains required reading in Kazakh schools today. His portrait is printed on the 2,000-tenge banknote. His quotes adorn bus stops, airport walls, and public plazas. In 2020, on the 175th anniversary of his birth, UNESCO joined Kazakhstan in commemorating him as a “great humanist of Central Asia.” [5]

More Than a National Symbol

It would be tempting to say that Abai has simply become Kazakhstan’s literary mascot. That would be a mistake.

He is not remembered out of obligation, but out of genuine relevance.

In the three decades since Kazakhstan gained independence from the Soviet Union, the country has wrestled with questions of identity. Russian remains widely spoken, and many Kazakhs — particularly in urban areas — are bilingual. Ethnic diversity is both a strength and a political complexity. The tension between tradition and progress is real.

In that context, Abai provides more than comfort. He provides clarity.

He was multilingual before it was policy. He was religious without dogma. Patriotic without xenophobia. A critic without cynicism. He modeled a form of nationhood that was elastic enough to stretch, but strong enough not to break.

“Abai was our first modern thinker,” says Saltanat Berdibek, a Kazakh writer and educator. “He asked us to be proud of our language, but also open to the world. He believed that being Kazakh didn’t mean looking backward — it meant looking inward, and then upward.” [6]

Today, Abai is finding a second life — not just in scholarly circles or official ceremonies, but in digital spaces.

Young Kazakhs quote his verses on TikTok and Telegram. Kazakh musicians have adapted his poetry into Q-pop lyrics. In Paris, a cultural center named after him offers workshops in Kazakh language and calligraphy. A recent AI project in Almaty even trained a chatbot on his writings — turning Abai into a digital sage. [7]

Perhaps this is the true test of cultural legacy: not how much a figure is praised, but how often they are used. Abai, it seems, remains usable — not as a tool of ideology, but as a partner in dialogue.

He is not frozen in bronze. He is alive in the conversations Kazakhstan is having about its future.

At a time when so many nations are caught in a crisis of meaning — uncertain how to balance history with change, or pride with humility — Abai offers a rare model.

He teaches us that national identity is not a weapon, but a whisper. That culture is not a museum artifact, but a muscle. That wisdom lies not in shouting, but in listening — to land, to literature, to one another.

For those of us beyond Kazakhstan’s borders, there is something quietly instructive in his life. He reminds us that greatness is not always loud. That reform does not always arrive with revolution. That poetry, when written with honesty, can outlast empires.

In one of his poems, Abai wrote:

“A human being must have a heart — a heart alive, not numb.”

In the end, that may be the legacy we need most.

*Jafar G Bua was former Field Producer of CNN Indonesia, base in Jakarta, Indonesia

References:

- UNESCO Official Page on Abai Qunanbaiuly, 2020 Commemoration.

https://en.unesco.org/commemorations/abai175 - Auezov, Mukhtar. Abai (Two-Volume Biographical Novel), Kazakh Literature Press.

- Abai Qunanbaiuly. The Book of Words (Kara Sozder). Trans. D. Banarsbayev. Astana: National Translation Bureau, 2019.

- Kassenova, Gulzhan. Interview, Nazarbayev University Public Lecture Series, 2022.

- The Astana Times, “Kazakhstan Commemorates 175th Anniversary of Abai,” July 2020.

- Berdibek, Saltanat. “Why Abai Still Matters in Modern Kazakhstan,” Eurasianet.org, 2023.

- Kazakhtelecom AI Labs, “AbaiBot: An AI Trained on 19th Century Wisdom,” Project Brief, 2024.